By Caroline O’Hare (she/her), Business Communications & Marketing

Celebrating International Women’s Day gives society a chance to take stock of how it has changed in terms of the opportunities now open to people identifying as women both professionally and socially. It gives us space to consider what has been achieved in enabling women to access greater parity as well as how far there is left to travel. It also highlights how this requires the delivery of equity rather than just equality.

It’s not where you start, it’s where you finish.

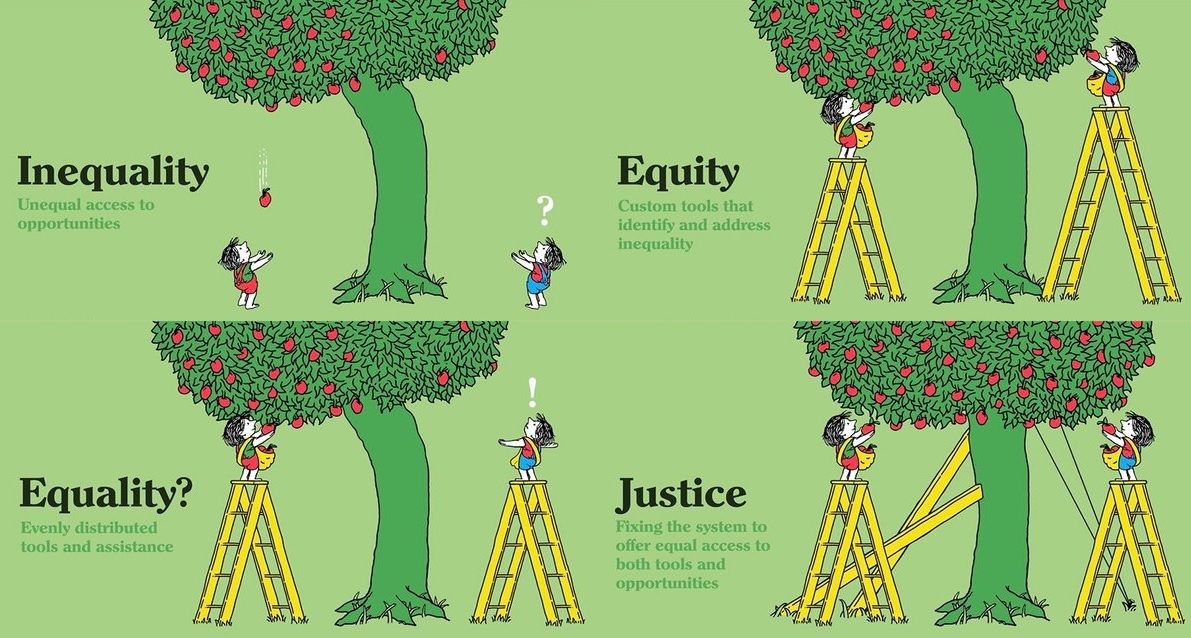

Equal opportunities are not enough. Indeed, whether these have yet been achieved is questionable. Equality means that everyone is given the same resources and opportunities from the outset. It assumes little difference in the needs of the individual to achieve a desired outcome. In contrast, equity recognises that individuals have different circumstances and allocates the resources and opportunities required for that individual to reach an equal outcome.

Equity disparities in STEM

While some progress has been made in attracting more women into STEM, large gender disparities remain. A recent study in 2020 comparing gender equality in terms of scientific author publication found the overall gender ratio was 27% female to 73% male. This marked an increase from 12% in 1955. STEM disciplines had the lowest gender ratios, with 18% female authors in Engineering, and 15% in Physics and Mathematics. So why has society been unable to move the dial more radically in bringing and retaining women in these fields?

It starts early.

By the time a school cohort reaches university, women are already significantly underrepresented in STEM. According to recent UCAS data, only 35% of STEM students in higher education in the UK are women. At a more granular level, the gender gap widens in key fields such as Engineering (16% women) and Computer Science (26% women). This nagging disparity is often explained by a lack of role models, cultures that exclude women, and persistent stereotypes about women’s intellectual abilities. Therefore, there are clearly more hurdles for women to overcome despite the equal opportunities on offer. More interventions are required at this stage to achieve equity.

The caring conundrum

The question of role models can be addressed in part by the caring conundrum. How do you sustain a career in a fast-moving technical field when the need for affordable and flexible childcare arises? A lack of accessible childcare is the extra hurdle that all working mothers must overcome. It is an issue not often equally faced by men. This was evident during the recent pandemic where the lack of available childcare was shown to disproportionately affected women. Retaining a career as a mother often depends on earning power, amenable grandparents or reducing working hours. When none of these are viable options, some women take the hit and put the brakes on their career. This ‘penalty on motherhood’ has been found to widen the gender pay and pensions gap.

Retraining returners

When the initial demands of motherhood subside, there is a valuable opportunity to train returners. This is not easy in any career but is extremely difficult in STEM. The fast pace of change in the sector means there is an enormous and often insuperable challenge in returning to the cutting-edge. Even those that don’t take a break but just reduce hours find that they have missed out on key career stepping stones, such as publications, from which they will never recover. There is little equity for women supporting a family relative to their male peers in terms of career outcome. In the face of such challenges some women are choosing to retire early or even take on second helpings of care-giving either with grandchildren as the amenable grandparent themselves, or by looking after elderly parents locked out of an expensive care system.

How to achieve greater career equity for women?

Without easily accessible and affordable childcare there will never be equity for women in the workplace, no matter how hard employers try to deliver it. For any chance of equity being delivered, there must be meaningful engagement on childcare by policymakers to drive tangible change. It is worth the effort and costs involved as it can prevent the damaging loss of highly qualified and experienced women from the economy. In turn, this will help to ‘grow’ the economic pie, as termed recently by a departing Prime Minister. Countries such as Sweden and Denmark that invest in accessible childcare retain more women in the workforce and so more taxpayers. In contrast, those that do not tackle the burdens of childcare such a Japan and Taiwan are experiencing shrinking economies alongside dwindling birth rates. The continued lack of affordable childcare not only drives inequity; it is a systemic barrier that is primarily penalising women. International Women’s Day serves not just to encourage us to embrace equity but to deliver justice.